Chain of Accountability

Definition

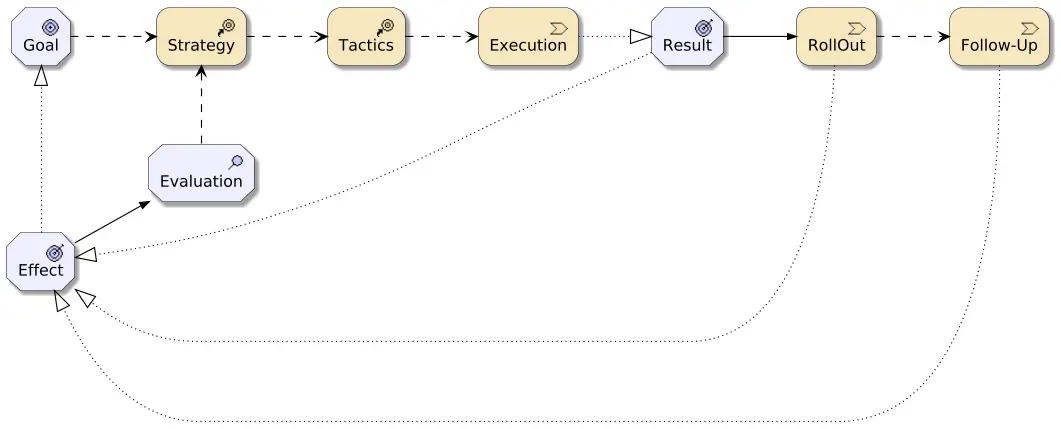

The Chain of Accountability is a structured hierarchy of roles and phases in the implementation of an idea, project, or plan. It ensures clear accountability at every step, from defining the goal to executing the strategy and tactics, and finally assessing the results and following up to maintain value. Each component plays a specific role in achieving the overall objective, ensuring coherence and responsibility throughout the process.

Key Components

Implementation of any idea can be broken down into key phases and components, each of which plays a bounded role, resulting in a coherent hierarchy of accountability. The goal of the model is to outline the different areas of responsibility. For each component in the chain, there is a clear outline of what is expected and who is responsible for it.

Chain Components

The Chain of Accountability consists of the following main components:

- Goal: Defining the target, or overall objective. It should be the guiding light that informs all other components, directing the decision-making process towards the desired outcome.

- Strategy: The high-level plan that outlines the approach to achieve the goal. It should be broad enough to allow for flexibility, but detailed enough to provide a clear direction.

- Tactics: A more specific, practical, description of the actions to be taken to execute the strategy. They should be concrete and actionable, providing a roadmap for the ’execution’ component.

- Execution: Actual implementation of the tactics, in accordance with the strategy, to achieve the goal. It is where the rubber meets the road, and the plan first comes into contact with reality. Most of the time, adjustments will be necessary to account for unforeseen circumstances.

- Result: The outcome of the execution, which should be measured against the goal to determine the success of the strategy. This is the culmination of all the previous components. Inspecting, and understanding, the result helps us see where the plan succeeded, and where it fell short.

- Rollout: After the result has been evaluated, it needs to be delivered to the stakeholders. In this phase, the focus is on stabilization, and ensuring that the benefits of the result are realized. The rollout phase is where the work is fully exposed to the world.

- Follow-up: After the rollout, it is important to follow up on the outcome, and ensure that the benefits are sustained. This phase is about maintaining the momentum, and ensuring that the plan continues to deliver value. It is also the time to gather feedback, track the impact of the results, and spend time reflecting on the process.

All of these steps contribute towards achieving an effect within the organization, which will (or will not) contribute to the overall goal.

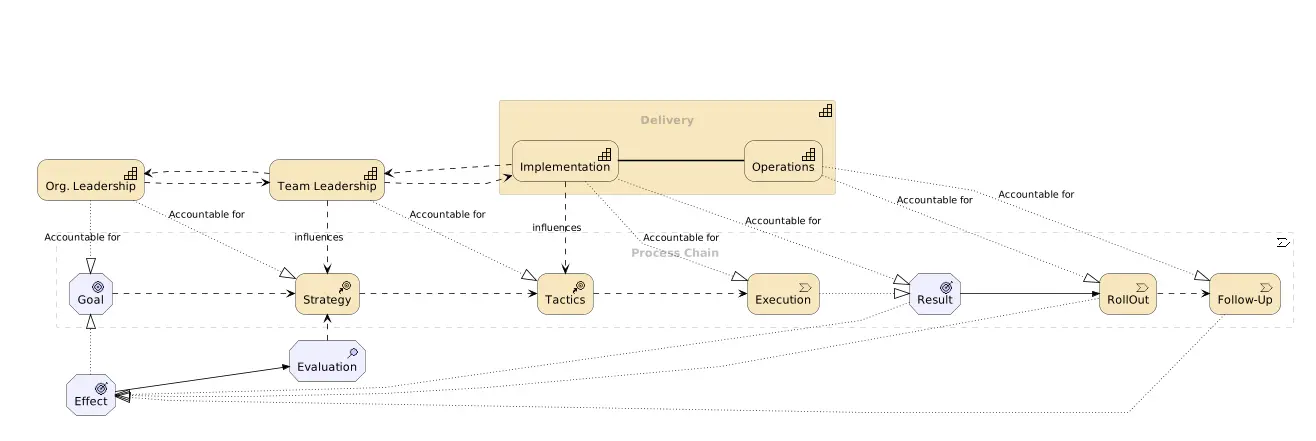

Accountability Scope

An organizational capability is a specific ability or capacity that an organization possesses to perform a particular task or function. They are realized by various elements of the organization, such as people, processes, and technology. This allows us to reason about “What an organization is capable of doing”, without having to dive into the specifics of the organization’s structure. These capabilities are mapped to the components of the Chain of Accountability, ensuring that each phase is assigned to the appropriate capability. The end-goal is that the right people are responsible for the right tasks, and that the organization’s capabilities are leveraged effectively to achieve the desired outcome.

People, or capabilities, relate to the components of the Chain of Accountability in different manners. Some bear the final responsibility for a component, whilst others are merely impacted by it. The following relationships are defined between the components and the capabilities:

- ‘Accountable for’: The people (or capabilities) who are ultimately responsible for the component. They are the ones who will be held accountable for the success or failure of the chain component.

- ‘Influences’: The people (or capabilities) who have a direct influence on the component. They are not directly responsible for it,

but their decisions and actions can impact the outcome. While they are not directly accountable, they play a significant role in the success of the process. - ‘Impacted by’: The people (or capabilities) who are affected by the component. They do not have a direct role in the execution or decision-making, but they are impacted by the outcome. Their work or responsibilities may change based on the results of the component.

Background

Origin

The concept of Chain of Accountability originates from the military chain of command, which is a hierarchical structure of authority in which decisions and commands flow from the top down. This structure ensures that each level of the hierarchy has clear responsibilities and accountability. Adapted to fit civilian organizations, the Chain of Accountability applies this structured approach to project and idea implementation, ensuring that each phase and component is clearly defined and has an accountability scope.

Application

The Chain of Accountability can be applied to a wide range of contexts, including business, project management, and personal development. By breaking down the flow of decision-making and implementation into clear phases and components, the model can help:

- Define clear goals and objectives.

- Identify and address gaps in the accountability chain.

- Align and communicate team/organizational composition and responsibilities within the project.

- Have a clear understanding of an individual’s role in the project, the responsibilities that come with it, and how it fits into the bigger picture.

Comparisons

Project Management Frameworks

The Chain of Accountability can be compared to project management frameworks like PRINCE2 and PMI’s PMBOK. These frameworks also emphasize structured phases and clear responsibilities. However, while PRINCE2 and PMBOK are comprehensive project management methodologies that include detailed processes and guidelines, the Chain of Accountability provides a more flexible, high-level approach focused specifically on accountability and the clear delineation of roles and phases.

Agile Methodologies

Agile methodologies like Scrum and Kanban emphasize iterative development and continuous improvement. While Agile focuses on flexibility, collaboration, and adaptability, the Chain of Accountability complements these methodologies by providing a clear structure for defining goals, strategies, tactics, execution, results, rollout, and follow-up. It ensures that even within the flexible and iterative Agile framework, there is a clear hierarchy of accountability.

Examples

The sixth of June 1944

- Goal: Liberate Western Europe from the grip of the fascist regime.

- Strategy: Launch a massive amphibious assault on the beaches of Normandy, sending every able-bodied person we can muster. Land on the beaches, and establish a foothold. Then push inland, making sure supply lines are secured.

- Tactics: Use SOE paracommandos to secure key bridges and roads to prevent the enemy from reinforcing their positions. Use amphibious personnel carriers to land infantry on the beaches, and make sure the infantry knows to disembark as soon as they hit the beach. Let the Royal Navy barrage the bulkheads on the beaches with artillery during the landing to soften up the enemy positions. Use the element of surprise to gain a foothold before the enemy can react.

- Execution: Bob Jenkins, a private in the 3rd infantry division, is on a barge preparing to land on Omaha Beach. He is part of the first wave and is tasked with securing a beachhead. When the barge nears the beach and the armoured hatch opens, the enemy opens fire. His squad is decimated before they can disembark. Private Jenkins is lucky enough to be standing near the back of the barge and is able to jump over the side as he was instructed to do. He is shot in the leg but manages to crawl to a nearby tank and uses it as cover to return fire.

- Result: The Allies secure a beachhead, but at a heavy cost. The first wave of the assault is decimated, and the follow-up waves are delayed. They succeed in holding the beaches, yet the advance inland is slow. The airborne divisions secure key bridges, but the paratroopers are scattered, and it takes time to regroup.

- Rollout: Reinforcements land, supply lines are secured, and the foothold grows. As the advance progresses, reservist troops and local militias reinforce and stabilize the reclaimed territory.

- Follow-up: The Allies liberate Western Europe, and the Marshall Plan is put into effect to rebuild the war-torn continent. A new international order takes shape, and the United Nations is founded to prevent future conflicts.

A corporate AI initiative

In a bustling corporate office, top management enthusiastically decided to “leverage the use of AI” to revolutionize their operations. However, their lack of understanding of AI and their unbridled excitement led them to bypass crucial planning stages. Development teams were instructed to dive into AI projects without clear strategies or actionable tactics. As weeks passed, it became evident that efforts were disjointed, resources were squandered, and progress was minimal.

Development teams, feeling the weight of unrealistic expectations and unclear directives, were thrown into a chaotic work environment. Each day brought more confusion as they attempted to piece together what management wanted, all while facing pressure to deliver results. The lack of direction led to frustration and disillusionment. Developers worked long hours on tasks that felt meaningless, often redoing work as priorities shifted without explanation. Morale plummeted as they realized their efforts were not only misaligned with the company’s objectives but also lacked any tangible impact, leaving them demotivated and questioning the purpose of their work.

Months passed, and the company’s AI projects remained stagnant, with no clear progress or results to show. The main delivered results were various chatbots and recommendation engines. As each of these projects was developed in isolation, they failed to integrate with existing systems and did not provide a consistent user experience. The chatbots were unable to understand complex queries, and the recommendation engines often recommended products from competing brands. In the end, the company’s ambitious AI initiative failed to deliver the promised results. To save face, management shifted blame to the development teams, accusing them of incompetence and lack of initiative. The teams, in turn, felt betrayed and abandoned, having been set up for failure from the start.

The absence of a Chain of Accountability in this scenario resulted in a breakdown of communication, direction, and alignment. With no coherent strategy or defined tactics, the teams struggled to align their execution with the company’s goals, resulting in wasted time and a significant financial drain.