Clean code

But it works! That’s all that matters, right?

Definition

Clean code refers to code that is easy to understand, maintain, and extend. It is written in a way that clearly communicates its intent, making it accessible to other developers and to the original author when revisiting the code after some time. Clean code minimizes complexity and avoids unnecessary clutter.

Key Components

- Readability: The code is easily readable and understandable by others.

- Maintainability: The code is structured in a way that makes it easy to maintain and modify.

- Expressiveness: The code clearly expresses its intent and logic.

- Simplicity: The code avoids unnecessary complexity and verbosity.

When developing software, it is tempting to focus solely on making it function correctly. Undoubtedly, functionality is paramount in software development. However, if you have ever worked on a substantial software project, you have likely spent a considerable amount of time reading and deciphering existing code. Even if you primarily work in isolation, confusion can still arise when revisiting your own code after a significant time-lapse.

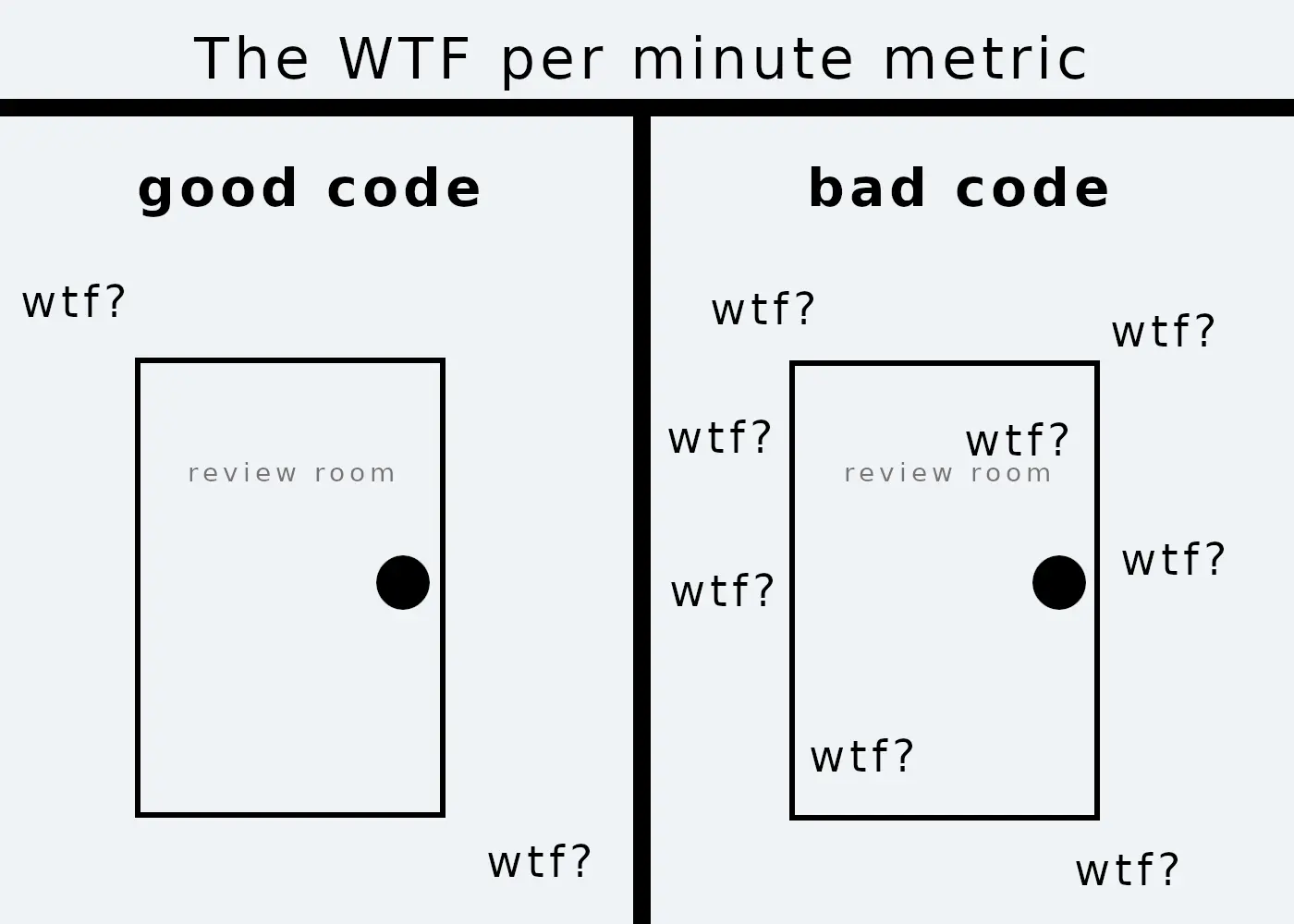

The main culprit for this confusion is often code that’s simply hard to understand. It lacks expressiveness or becomes overly verbose. One helpful metric to gauge the cleanliness of your code is humorously known as the ‘WTFs per minute metric,’ inspired by a well-known cartoon that has been recreated numerous times.

Writing clean code does more than please your colleagues; you are doing your future self a favour. Projects inevitably evolve, and what was once insignificant can become critical to the application’s success. When the code handling this functionality is messy, adapting to changing requirements can feel like a descent into chaos. So, do yourself a favour, and strive to keep your code comprehensible at a glance.

Your colleagues and your future self will thank you.

Background

Origin

The concept of clean code has been emphasized by many influential figures in software development. Books like “The Clean Coder” by Robert “Uncle Bob” Martin, “Refactoring” by Martin Fowler and “The Pragmatic Programmer” by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas have highlighted the importance of writing clean, maintainable code. It was also mentioned in the “C++ Complete Reference” by Herbert Schildt, where he stated that “a program should be written for people to read—and only incidentally for machines to execute.”

Application

Clean code is essential in software development as it facilitates collaboration, reduces the risk of introducing bugs, and makes the codebase easier to work with over time. It is particularly crucial in large projects where multiple developers are involved, and in projects that are expected to evolve and grow.

Many of us have encountered advice from experienced developers urging us to ‘write clean code.’ While the idea is straightforward —clean, understandable code is easier to extend and maintain — the challenge lies in understanding how to achieve it. Seasoned developers often seem to possess an intuitive sense for what constitutes ‘clean’ code, a skill that you will develop over time. Yet, when you’re just starting out, it is invaluable to have a set of best practices to guide you in evaluating your code’s cleanliness.

Comparisons

The idea of clean code is closely related to:

- the principles of software craftsmanship, which emphasize the importance of writing code that is not only functional but also well-crafted.

- the concept of technical debt, as clean code helps to reduce the accumulation of technical debt by making it easier to maintain and extend the codebase.

- the practice of refactoring, which involves restructuring existing code to improve its readability, maintainability, and extensibility.

Examples

Some simple guidelines

- Readability: Using descriptive variable and function names, writing comments where necessary, and organizing code logically to make it easy to follow.

- Maintainability: Structuring code in small, reusable functions or classes, adhering to coding standards, and avoiding hard-coding values that might change.

- Expressiveness: Writing code that clearly shows its purpose without requiring additional explanation. For example, using meaningful names and avoiding cryptic abbreviations.

The power of Naming

In a surprising amount of fairy tales, myths, and legends the “power of naming” is an ancient magical ability that allows you to control things if you just know how it is really called. Programming is not much different. If the entities and variables you work with have revealing names, a confusing piece of code becomes very clear. This clarity is achieved by simply renaming things to be expressive, a feat most modern IDEs can do for you at little cost.

Take a look at the code below:

public class Main {

public static final int MRIG = 21;

public static final int AMOUNT = 10;

public static final int MAX = 10;

private final int[] down = new int[MRIG];

private int cr = 0;

public void go(int input) {

down[cr++] = input;

}

public int calcResult() {

int result = 0;

int counter = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < AMOUNT; i++) {

if(caseOne(counter)) {

result += 10 + bonusOne(counter);

counter += 1;

} else if(caseTwo(counter)) {

result += sum(counter) + bonusTwo(counter);

counter += 2;

} else {

result += sum(counter);

counter += 2;

}

}

return result;

}

private boolean caseOne(int in) {

return down[in] == MAX;

}

private boolean caseTwo(int in) {

return sum(in) == MAX;

}

private int sum(int in) {

return down[in] + down[in + 1];

}

private int bonusTwo(int in) {

return down[in + 2];

}

private int bonusOne(int in) {

return down[in + 1] + down[in + 2];

}

}

Do you understand what it does? Did you recognize what real-life activity it is representing? Let’s look at the exact same piece of code. Only this time, we will use better names for methods, fields, and variables.

public class Game {

public static final int MAXIMUM_ROLL_IN_GAME = 21;

public static final int AMOUNT_OF_FRAMES_IN_GAME = 10;

public static final int MAX_PINS_PER_FRAME = 10;

private final int[] pinsKnockedOver = new int[MAXIMUM_ROLL_IN_GAME];

private int currentRoll = 0;

public void roll(int pinsRolledOver) {

pinsKnockedOver[currentRoll++] = pinsRolledOver;

}

public int score() {

int score = 0;

int rollCounter = 0;

for(int frame = 0; frame < AMOUNT_OF_FRAMES_IN_GAME; frame++) {

if(isStrike(rollCounter)) {

score += 10 + strikeBonus(rollCounter);

rollCounter += 1;

} else if(isSpare(rollCounter)) {

score += sumOfPinsKnockedOverInFrame(rollCounter)

+ spareBonus(rollCounter);

rollCounter += 2;

} else {

score += sumOfPinsKnockedOverInFrame(rollCounter);

rollCounter += 2;

}

}

return score;

}

private boolean isStrike(int rollCounter) {

return pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter] == MAX_PINS_PER_FRAME;

}

private boolean isSpare(int rollCounter) {

return sumOfPinsKnockedOverInFrame(rollCounter) == MAX_PINS_PER_FRAME;

}

private int sumOfPinsKnockedOverInFrame(int rollCounter) {

return pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter]

+ pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter + 1];

}

private int spareBonus(int rollCounter) {

return pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter + 2];

}

private int strikeBonus(int rollCounter) {

return pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter + 1]

+ pinsKnockedOver[rollCounter + 2];

}

}

To a compiler, both code snippets are identical. Humans, however, are not computers (even though most developers would like them to be). Being human, we understand text fragments better if we are given enough context and if we understand a majority of the words that are being used. Good code should allow anyone with a fundamental understanding of the language of choice to understand what is happening at a glance. The older you get, the harder it becomes to keep a large stack of working knowledge in your head. If your code requires you to hold a lot of this knowledge just to be able to understand what is going on, it is probably not very well written.

The additional benefit of having your code be understandable at a glance is most noticeable when you are interrupted. Having to stop what you are doing and focus on something else, is what we call a context switch. Research has shown that regaining focus takes longer than expected; some researchers estimate the refocus window at roughly 20 minutes. The more knowledge you are required to hold on to, the harder it will be to refocus on what you were doing before the interruption happened.