Ikigai

Your reason for being, discovered through living

Definition

Ikigai (生き甲斐) is a Japanese word that translates loosely to “a reason for being”. It refers to the experiences, values, and activities that make life feel worthwhile. These are not necessarily grand life missions, but also small, meaningful patterns that bring joy, contribution, or personal growth.

Key Components

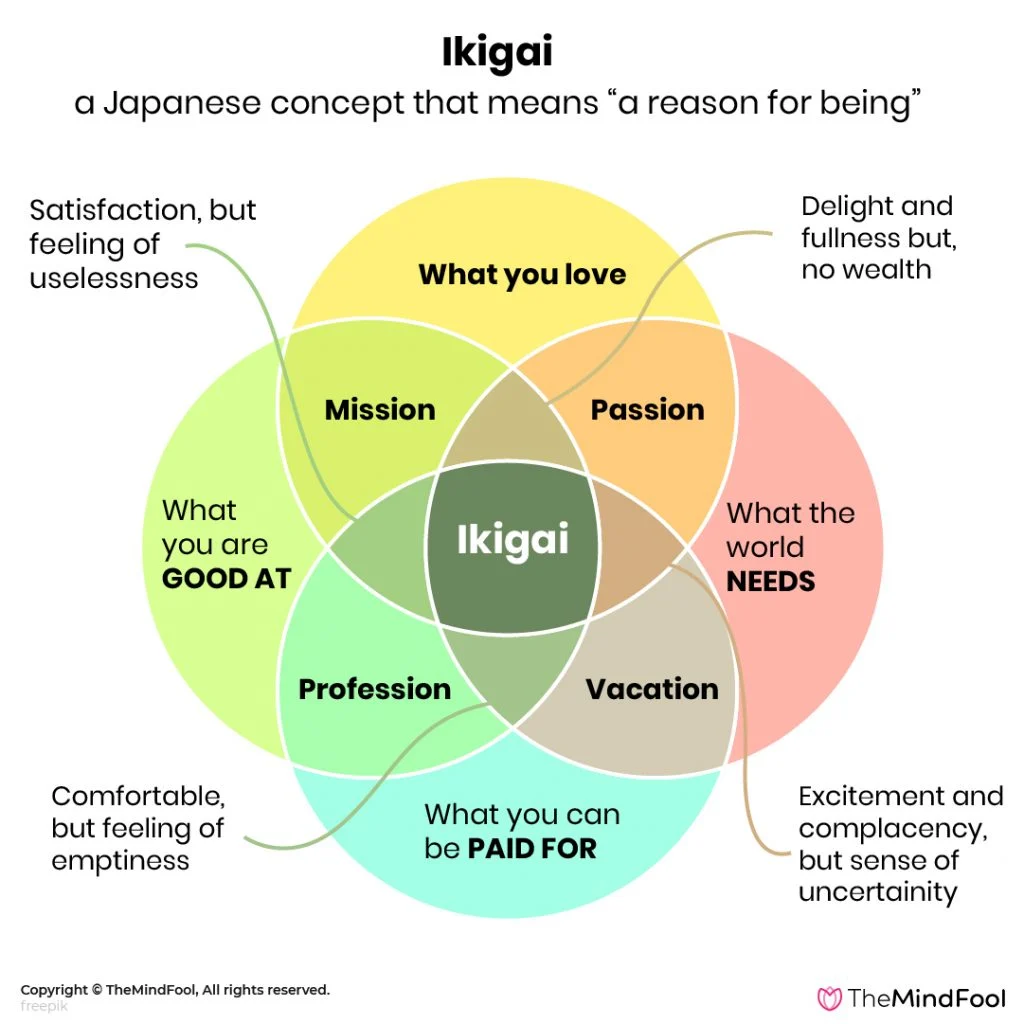

In modern interpretations, Ikigai is often visualized through a four-circle diagram representing:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can be paid for

At the centre of these lies your Ikigai: the area where joy, skill, contribution, and sustainability intersect. This visual model is popular in coaching and self-development circles, particularly for those reflecting on career choices or life direction.

Where all four circles align, you find your ‘Ikigai’. This is often described as a state of flow, where you are fully engaged in activities that resonate with your values and aspirations. You love what you do, you are good at it, it contributes to the world, and it pays the bills.

Right outside the centre, there are areas of partial alignment, where a few of the circles overlap. These areas can be seen as different types of engagement or fulfillment:

- Passion: What you love + what you are good at

- Mission: What you love + what the world needs

- Vocation: What the world needs + what you can be paid for

- Profession: What you are good at + what you can be paid for

These areas can be fulfilling in their own right, but they may not provide the same sense of completeness as Ikigai. For example:

- Delight and fullness but without pay

- Excitement but feeling of uncertainty

- Comfortable but feeling of emptiness

- Satisfaction but no sense of impact

Background

Origin

The word Ikigai combines iki (life) and gai (value or worth). It originates from Japanese cultural and linguistic roots, particularly in Okinawa, where it reflects a more embedded, humble sense of life purpose than the Western ideal of grand calling or career fulfilment.

Traditional interpretations see Ikigai not as a destination but as a state of being: a felt sense that life is worthwhile, supported by relationships, small joys, and meaningful patterns. It is as much about presence and care as it is about ambition or success. The now-famous four-circle model of Ikigai is a Western abstraction — helpful for career planning, but not entirely aligned with the concept’s philosophical grounding. It tends to treat Ikigai as something to find and fix, rather than nurture and evolve.

Application

Ikigai is often used as a reflection tool for bringing more intention and coherence into how we live and work. You might explore it:

- As part of career transitions, life design, or burnout recovery

- When something feels off, but it’s unclear what

- To reflect on what brings meaning in everyday moments

- In coaching or mentoring to uncover deeper motivations

tip: Ikigai is not a fixed destination

While the Venn diagram can be helpful, it’s important not to confuse Ikigai with a singular, perfect path to be discovered. In traditional Japanese thinking, Ikigai is something cultivated, not optimised — it may grow from a daily ritual, a sense of responsibility, or a practice honed over time. You can move closer to Ikigai not only by finding new roles, but by discovering new dimensions of meaning in what you already do.

There is also a strong resonance between Ikigai, and the Stoic principle of amor fati — the idea of loving one’s fate. While Ikigai invites us to align our actions with joy and meaning, amor fati teaches us to embrace all that life brings, including hardship, as inherently worthwhile. Both philosophies encourage presence, acceptance, and the intentional shaping of meaning within the lives we already live.

Comparisons

Ikigai vs. Purpose vs. Calling

While Ikigai, purpose, and calling all relate to meaning and direction, they differ significantly in tone, structure, and cultural roots. The table below outlines their contrasts:

| Aspect | Ikigai | Purpose | Calling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tone | Gentle, grounded, evolving | Ambitious, outward-facing | Spiritual or vocational in tone |

| Cultural Origin | Japanese, relational, rooted in daily life | Western, often associated with legacy or impact | Often religious or deeply personal in origin |

| Change Over Time | Dynamic and fluid — changes with life seasons | Can evolve, but often framed as a fixed direction | Typically seen as fixed or “discovered” |

| Scale of Meaning | Can be small (daily joy) or large (life work) | Usually large — world-changing or goal-oriented | Often binary — you have it or you don’t |

| How It Emerges | Cultivated through attention, care, and reflection | Defined by goals, beliefs, or external missions | Experienced as a calling, vocation, or inner pull |

| Emphasis | Balance between self and others, being and doing | Impact on others or the world | Personal fulfilment and spiritual alignment |

| Practical Use | Guidance for living meaningfully in the present | Driver for long-term vision or strategic focus | Source of motivation and identity |

Each model can prove useful, depending on your context: Use Ikigai when seeking presence and integration, purpose for strategic alignment and outward impact, and calling when driven by personal conviction or inner voice.

Ikigai vs. Amor Fati

Another philosophical idea that shares deep resonance with Ikigai is the Stoic concept of amor fati — loving your fate. Where Ikigai invites us to find or cultivate meaning in the patterns of our daily life, amor fati encourages us to learn to love those patterns even when they are painful, messy, or unexpected.

Both philosophies:

- Emphasise presence over escapism

- Suggest meaning can be cultivated, not hunted

- Invite us to engage with the life we have, not chase one we don’t

The key distinction is emphasis:

Ikigai focuses on bringing meaning into your actions and aligning with joy or contribution. Amor fati is about bringing acceptance into your attitude and aligning with reality, even hardship.

Together, they offer the wise lesson:

Live with intention — and love what unfolds.

Examples

Snapshot Scenarios

- A craftsperson who finds satisfaction in daily practice, serves a community need, and earns a modest living may be deeply aligned with Ikigai — even if their work isn’t glamorous.

- A high-performing executive who feels disconnected and restless may be misaligned — especially if their work lacks love, meaning, or social contribution.

- A retiree who tends their garden, shares wisdom, and enjoys time with grandchildren may be living closer to Ikigai than someone chasing external validation.

- A volunteer coordinator who thrives on organising community events finds meaning in bringing people together, even if the role is unpaid and informal.

- A school teacher whose joy comes from student growth and mentorship, even in a constrained system, may find Ikigai through impact, not perfection.

Extended Example: The Mid-Career Developer

Janice is a senior software engineer in her mid-30s. Technically skilled and well-compensated, she finds herself dreading Monday mornings. The work is stable, but repetitive. Her contributions feel distant from real impact, and her enthusiasm has waned.

After a difficult project ends, she takes time to reflect. She realises she still loves solving problems and mentoring younger devs. Instead of quitting her job entirely, she proposes a new internal role: part technical lead, part mentor for junior engineers, with space to shape onboarding and developer tooling. Over time, she also contributes to open-source tools her team uses.

Her core job title hasn’t changed much, but her relationship with her work has. She now feels challenged, connected, and appreciated. Her Ikigai didn’t require a dramatic pivot — it emerged by reshaping her current context into something more meaningful.

Extended Example: The Teacher Who Drifted Off Course

Eric is a gifted teacher who started his career with passion and purpose. He loved watching students grow, found deep joy in preparing lessons, and felt proud of the lives he influenced. Over time, though, he began to feel undervalued by his institution and peers, particularly when comparing his salary to friends in the private sector.

Tempted by better pay, he moved into a series of administrative and consultancy roles within the education system. The money improved, and his title sounded impressive — but each step pulled him further from the classroom, and from the interactions that had once energized him. He became disillusioned, despite external signs of success.

Then, unexpectedly, a cousin asked him to help tutor her teenage son who was struggling with maths. That single hour rekindled something he hadn’t realised was missing: the spark of shared curiosity, the satisfaction of seeing someone “get it.” It reminded him why he started teaching in the first place.

Soon after, he began volunteering in a local after-school programme, and eventually returned to part-time teaching. He now balances strategic education projects with direct student engagement and mentoring. For Eric, his Ikigai hadn’t disappeared — it had just been buried under layers of professional optimisation. Rediscovering it meant stepping away from the pursuit of prestige and reconnecting with the simple joy of helping others learn.