Traceable decisions

Problem statement

You are making decisions in your software development process, and spending considerable amounts of time communicating them to your team, management, and business stakeholders. These parties are not always aware of the context in which the decision was made, the trade-offs that were considered, making it hard for them to evaluate the impact of their own decisions on the project.

Intent

Use a structured way to document the decisions made in your software development process. This will allow you to track the decisions made, and why they were made. It will also allow you to evaluate the impact of these decisions, and to communicate them to the relevant stakeholders in an asynchronous way. This will allow you to spend less time in meetings or answering questions, and more time on work that requires focus ( Talk less, Do more ).

Solution

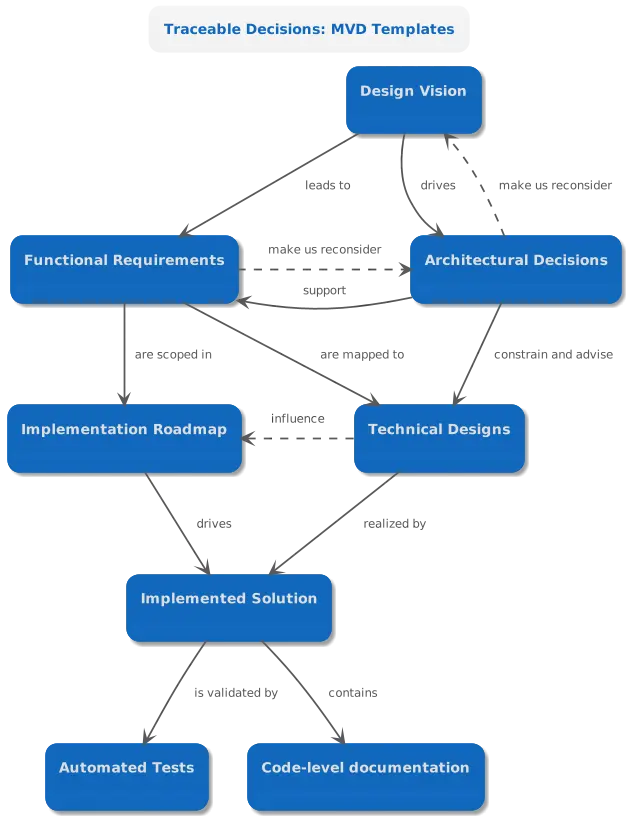

Write “just enough design documentation” to document the decisions made in your software development process. Make sure you keep the documentation as light-weight and accessible as possible. The aim is to make the documentation useful, not to make it complete. You should generally start by writing down some high-level design documentation, outlining the project goals, the key stakeholders, and the context in which you are working. This will help you when trade-offs need to be made, to evaluate the impact of decisions, and to communicate with various stakeholders. The high-level documents should be readable by anyone, and are an excellent visual aid to discuss ideas and challenges. As your team matures and develops other needs, you can add more detailed documents, such as functional requirements, technical designs, and drill-downs of particularly complicated aspects of the system.

Contextual forces

Enablers

The following factors support effective application of the practice:

- Your team is distributed, and you need a way to communicate decisions asynchronously.

- You are working in a complex environment, with many stakeholders and dependencies.

- You are willing to invest time in learning new tools and techniques.

- Your organization is looking for ways to avoid wasteful meetings.

- Your team is willing to invest time in documenting decisions.

- Your organization values transparency and accountability.

Deterrents

The following factors prevent effective application of the practice:

- You are working in a fast-paced environment, where decisions are made on the fly.

- Your organization values “talking about things” over “getting things done”.

- You are a one-person team, and see no need to keep track of your decisions.

- There is no tooling available to document decisions in a structured way.

- Your organization has a culture of “blame and shame”.

- Your team is not used to writing documentation.

Application

Considerations

- Over-documentation: There is a risk of creating too much documentation, which can become overwhelming and counterproductive.

- Resistance to Change: Teams not used to documentation may resist adopting this pattern.

- Time Investment: Initial setup and continuous maintenance of documentation require significant time and effort.

- Tool Dependence: The effectiveness of this pattern heavily relies on the availability and usability of documentation tools.

Mitigation strategies

- Set Clear Guidelines: Establish clear guidelines on what needs to be documented and what does not. Focus on essential information to avoid over-documentation.

- Start Small: Begin with minimal documentation and gradually increase complexity as needed. Introduce the pattern gradually, allowing the team to adapt to the new process over time. Provide training and support to ease the transition.

- Automate Where Possible: Use tools and automation to streamline the documentation process, reducing the manual effort required.

- Regular Reviews: Conduct regular reviews of the documentation to ensure it remains relevant and up-to-date. Remove outdated or unnecessary information.

Examples

Just-enough design documentation templates

Writing design documentation can be a daunting task. It is often seen as a necessary evil, and as a result, it is often done poorly. The result of this is that the documentation is not useful, stays unmaintained, and is not used by the team. This is a shame, as good design documentation can be a powerful tool to align the team, to communicate with stakeholders, and to make sure that the system is built consistently.

To make the process of writing design documentation easier, and to make sure that the documentation is useful, the templates below can be used as a basis for your own documentation needs. Be sure to adapt them to your own context, and to only use the parts that are useful to you. Feel free to remove parts that make no sense to you, add parts that are missing, and to use these templates in any way that helps you.

tip: Most organizations have their own standards for design documentation. These standards can range from “You must use confluence” to “Just write it down on a napkin and take a picture of it”. Make sure to adhere to these standards, and to use the tooling provided by your organization as best you can. Most modern tools (confluence, Jira, Miro, GitHub, Zapier, …) have ways to create templates, add automation, and to link to other platforms. Use these features to make your life easier, and look for ways to adapt the provided templates to be used inside these tools.

I recommend to start by using the Design Vision Template, and Functional Requirements Template to create a high-level overview of the system. As your project matures: Refine these, and add other documents as needed. Just make sure to only write what is needed, and what is likely to remain unchanged for a significant amount of time. For instance, adding a detailed technical diagram of all the classes in your system is likely to be a waste of time, as it will be outdated as soon as you start coding. Instead, focus on the high-level architecture, the key components, and the most important trade-offs. Your aim is for the documentation to be useful, not for it to be complete.

Design Vision Template

This template can be used as a basis to create a high-level architectural vision document. It is intended to provide an overview of the most important aspects of the system architecture.

It aims to be understandable to all stakeholders, not just technical people.

It answers the questions: “What are we trying to do, why are we trying to do it, and what is our vision on how to do it?”

# High-level architectural vision

This document describes the high-level architectural vision for the system. It is intended to provide an overview of the most important

aspects of the system architecture. It aims to be understandable to all stakeholders, not just technical people.

## Business Goal Statement

> Describe the business goals that the system is intended to support. This should be a high-level description of the problem that the system

> is intended to solve, and the benefits that are expected to be gained from it. Stick to the overarching goals, and avoid going into too

> much functional detail. This section explains the "why" of the system, not the "what". It should focus on the objectives of the stakeholders,

> and the expected benefits the system will give them. This section should contain a single, clear, and concise statement. It can then

> elaborate on it by providing more context, or giving a rationale behind the business vision statement. This is a good place to list the

> [key objectives and results (OKRs)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Objectives_and_key_results) that the system is intended to support.

>

> As an example: when building a webshop, the business goal statement would be something like "In order to

> compete with third-party vendors and suppliers, Hardware Company ABC wants to provide a platform to allow international customers

> to purchase products online.".

For a more detailed breakdown of the business goals into functional requirements,

refer to the [Functional Requirements Overview](./functional_requirements.md).

## Desired Quality Attributes

Within systems engineering, quality attributes are realized non-functional requirements used to evaluate the performance of a system.

TThese are sometimes named architecture characteristics, or "ilities" after the suffix many of the words share. They are usually

architecturally significant requirements that require architects' attention. This section will describe the quality attributes (QA) that

were deemed most important for the system, and that will be used to guide the architectural decisions.

> Replace the placeholders with the actual quality attributes that are most important for the system.

> As QAs are not a fixed convention, you have a lot of wiggle room as an architect to define what you mean by them.

> I advise you to search for an overview of quality attributes, select a few of them that speak to you, and select up to five of these

> as important to your system. Describe the quality attribute in a very concise manner, and make sure that it is understandable to

> non-technical readers. If you want to go into more detail, you can add a rationale section to explain why you selected these QAs.

* **quality attribute name**: short description of the quality attribute

* **quality attribute name**: short description of the quality attribute

* **quality attribute name**: short description of the quality attribute

For a more detailed breakdown of the architecturally significant decisions, taken to support the aforementioned Quality Attributes, refer to

the [Architecture Decision Records](./adr.md).

## Organizational Context

> As an architect, you are not working in a vacuum. You are part of an organization, and your work is influenced by the organization's

> structure, culture, and processes. This section describes the organizational context in which the system is being developed. It should

> describe the key stakeholders, their roles, and how they fit into the organization. It should also describe the development process that is

> being used, how the developer teams are organized, and how the system fits into the overall IT landscape of the organization.

> Most importantly: it should describe relationships and dependencies between the development teams and other teams in the organization.

> Using the [Team Topologies](https://teamtopologies.com/) model can be a good way to describe the organizational context in a semiformal,

> structured way.

## Solution Overview

This section describes the high-level solution to the problem. It will stick to describing the key components of the system, how they

interact, and what the system as a whole is supposed to do. It will also describe the key technologies that will be used, and the envisioned

interfaces used by the stakeholders. The breakdown of the functional requirements into technical components will be described in the

[Functional Requirements Overview](./functional_requirements.md), and is not part of this document.

> Describe the high-level solution to the problem. This should be a non-technical description of the system, focusing on the key components.

> If you use the [C4-Model](https://c4model.com/), this would include the System Context and the Container diagrams.

Functional Requirements Template

# Functional Requirements

## Business Statement

Briefly describe the problem that the system is intended to solve. How it aims to solve it, and what the expected benefits are.

Write this in a way that is understandable to all stakeholders, not just technical people. Think of it as your 2-minute management pitch on which you can expand if people are interested.

## Stakeholders Overview

A short summary of the key people / personas that will interact with the system in some way. Be sure to include the developers, testers, and

your organization, as well as the envisioned customers and end-users.

| Persona name | Description | Cares about |

| --- | --- | --- |

| Developers | Technical staff implementing new features, and maintaining the code. | Clarity in code, easy-to-read documentation, ability to be creative, speed of change |

## Top-level functional requirements

> A very short list of the most important features that the system must have. These are the features that are most important to the

> stakeholders, and that will be used to prioritize the work later on. You can format these as a bullet list, or as a table.

> It is advisable to add an indication of the relative importance of each feature, to help with prioritization.

> A light-weight way to do this is to use the MoSCoW method, where you indicate if a feature is `Must-have`, `Should-have`, `Could-have`, or

> `Won't-have`.

| feature identifier | MoSCoW | Status | Description |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Name or UUID | `Must-have` | `Accepted` | A short description of the feature, or link to the detailed FR's |

| Name or UUID | `Should-have` | `Proposed` | A short description of the feature, or link to the detailed FR's |

| Name or UUID | `Should-have` | `Proposed` | A short description of the feature, or link to the detailed FR's |

| Name or UUID | `Could-have` | `Proposed` | A short description of the feature, or link to the detailed FR's |

| Name or UUID | `Won't-have` | `Rejected` | reason: Unrealistic, and unneeded |

## Detailed functional requirements

This section explains a selection of the most important functional requirements in more detail. It should provide enough context for the

reader to understand what the system is supposed to do, and how it is supposed to do it. The target audience is business analysts,

developers, and architects.

> Describe your most important functional requirements in more detail. Add as much context as you wish, and describe the functionalities as

> detailed as required so your colleagues/team/stakeholders understand them easily. You can use a table, a bullet list, or a more narrative

> style. Make sure to include the rationale behind the requirements, and the expected benefits of implementing them.

> If you have a lot of requirements, you can split them up into separate documents, and link to them from here. If you intend to write

> detailed implementation designs (such as exemplified in the `Technical Design Template`) you can link those as well.

### FR-001: Requirement Name

**status**: `Proposed` / `Accepted` / `Rejected` / `Planned` / `Implemented`

**MoSCoW**: `Must-have` / `Should-have` / `Could-have` / `Won't-have`

> Describe the requirement in detail. What is the expected behaviour of the system? What are the inputs and outputs?

>

> A good way to structure this is to use a short statement in the *"As a ... I want to ... so that ..."*-format, as it helps to keep the

> requirement focused on the stakeholder needs.

>

> Make sure to include the rationale behind the requirement, and the expected benefits of implementing it.

> Consider adding a BPMN diagram, a sequence diagram, or a flowchart to illustrate the requirement.

Architecture Decision Records Template

# Architecture Decision Records

## ADR-001: Title

**status**: `Proposed` / `Accepted` / `Rejected`

**date**: YYYY-MM-DD

### Context

> Why do we need to make this decision?

> Briefly describe the context in which the decision is taken, and the forces at play.

> Try to describe the problem you are faced with, as well as the current state of the application and the development team.

### Decision

> What have we decided to do?

> Keep this section short and to the point, avoid going into too much technical detail.

> Refer to the rationale section for the trade-off breakdown, or to lower-level technical designs for implementation details.

### Rationale

> Why is this decision being made? What are the forces at play? What are the trade-offs? What are the implications of this decision?

> Refer to functional requirements and design vision for context.

### Envisioned Consequences

> What do we expect to happen as a result of this decision? Try and correlate these to your architectural vision and NFRs if possible.

> Make sure to outline both positive and negative consequences of the choice you made.

> The rationale sections should provide enough context to indicate why the trade-offs were accepted.

>

> **hint:** You can use a framework such as [AMMERSE](https://www.ammerse.org/) to make these impacts easier to write, and to ensure a

> consistent structure across your ADRs.

### Considered Alternatives

> What other options did you consider? Why did you decide against them?

> Do not go into too much detail, a bullet point list with a brief description of the alternative, and a single sentence as to why it was not chosen

> is sufficient.

Implementation roadmap Template

# Implementation Roadmap

> Describe the high-level implementation roadmap for the system. What are the key milestones, and what are the expected deadlines?

> What are the most important features that need to be implemented, and in what order? Concisely describe the rationale behind your

> milestone goals, and why they were split in this way.

>

> Add a Gant chart, or block diagram to illustrate the roadmap. Make sure to include the most important milestones, and any external

> dependencies if present.

## Milestone 1: Goal statement

* **status:** `BACKLOG` / `IN PROGRESS` / `DONE` / `CANCELLED`

* **deadline:** YYYY-MM-DD

* **expected completion date:** YYYY-MM-DD

* **expected effort required:** ? Workdays - ?? Workdays

> Describe the intention of this milestone. What are you trying to achieve, and why is it important?

> What will be the impact of this milestone on the system as a whole, and on the stakeholders?

> How will you know when this milestone is completed? What are the key deliverables?

## Milestone 2: Goal statement

* **status:** `BACKLOG` / `IN PROGRESS` / `DONE` / `CANCELLED`

* **deadline:** YYYY-MM-DD

* **expected completion date:** YYYY-MM-DD

* **expected effort required:** ? workdays - ?? workdays

> Describe the intention of this milestone. What are you trying to achieve, and why is it important?

> What will be the impact of this milestone on the system as a whole, and on the stakeholders?

> How will you know when this milestone is completed? What are the key deliverables?

Technical Design Template

A technical design document is intended to outline technical details of a systems structure and implementation. It provides a lower-level description of how the system is supposed to work, and how features are to be implemented. It translates the higher-level design vision, functional requirements, and architectural decisions into a “plan of approach”. If those documents are the mission statement, and the strategy, the technical design is the battle plan. It is primarily oriented at being useful to developers, but should not be so detailed that it becomes outdated or takes away the possibility of independent thought during implementation.

# Technical Design: Feature Name

## Context

> Describe the context in which this feature is being developed. What are the forces at play, and what are the constraints?

> This section should describe the problem you are trying to solve, and the current state of the application. Refer to sections from the

> functional requirements and design vision documents where applicable (and to avoid repeating yourself).

## Acceptance Criteria

> Describe the acceptance criteria for this feature. What are the conditions that need to be met for this feature to be considered done?

> Make sure to include both functional and non-functional requirements in this section. Write them in a way that is understandable to

> everyone involved, and that can be used as a basis for testing. Using minimal SMART objectives can be a good way to structure this section.

> If your project has a Definition of Done, consider including or referencing it here.

## Design

### Overview

> Describe the high-level design of the feature. What are the key components, and how do they interact?

> This section should provide a high-level overview of the feature, and should be understandable to all stakeholders, not just developers.

### Implementation Considerations

> Describe the key implementation considerations for this feature. What are the trade-offs that were made, and why?

> This section should provide enough context for the developers to understand the design decisions that were made, and to implement the feature.

> It should also provide enough context for the stakeholders to understand the impact of the feature on the system as a whole.

### Cross-cutting concerns

> Describe the cross-cutting concerns that are relevant to this feature. What are the security, performance, and scalability considerations?

> These are concerns that are relevant to the system as a whole, though they do not directly contribute to the core functionality of the

> system. They should be taken into account when implementing any feature, both while estimating and executing the work.

> As always, remove any header that is not relevant to your feature, and add any that are missing. It helps to reference the relevant

> high-level documents in this section, to provide context to the reader and avoid repeating the same rationale (DRY principle).

#### Security

#### Performance

#### Deployment

#### Auditing and Logging

## Planning

> A bullet list with some high-level planning information. This can include the estimated development time, the estimated rollout time, time

> to complete the testing cycle, the urgency of the feature, and the estimated added value. Feel free to add metrics that are relevant to

> your decision-making process. This section can be omitted if these metrics are not relevant to your project or if they are being tracked

> in other tooling (e.g. Jira, excel). If dependencies are present, make sure to list them here.

* **Estimated development time:** ? Workdays - ?? Workdays

* **Estimated rollout time:** ? Days

* **Urgency:** `high`, `medium`, `low`

* **Estimated added value:** `high`, `medium`, `low`

* **Depends on:** ???

Criticism & Clarifications

- Templates help but cannot replace conversations—schedule checkpoints for decisions that carry large risk.

- Documentation that no one reads is waste; archive or delete artefacts that no longer guide active work.

- Keep security and confidentiality in mind when recording sensitive trade-offs or stakeholder debates.